The Royal Ballet’s Sleeping Beauties have just drawn to a close, giving way to the usual Christmas special of Nutcrackers. Notice anything in common? Both are Petipa ballets, both are amongst the safest for box office purposes, with blockbuster works such as Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, their lavish costumes, orchestral music and vast ensemble of dancers, always in demand with regulars and first timers alike. Petipa ballets may be overly done, but they remain definitive classics, with great choreography which survived more or less unscathed over the years since their Imperial Ballet days.

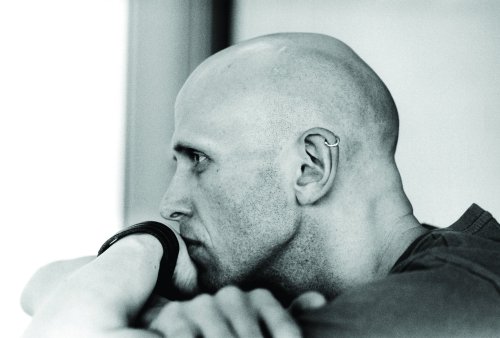

In this post we look at Marius Petipa and the scale of his achievements. This Franco-Russian choreographer changed the face of ballet and created masterpieces – the first ballets that come to mind when one thinks classical dance – that continue to inspire generations of dancers, new choreographers and audiences.

Marius Petipa in a Nutshell

Victor Marius Alphonse Petipa was born on 11 March of 1822 in Marseille son of an actress, Victorine Grasseau, and a ballet dancer (and eventually ballet master) Jean Antoine Petipa. Petipa got drawn into the ballet world early on, starting to train at age 7 in Brussels where his family had moved to. At the time, Petipa attended the Brussels Conservatory, where he studied music. He went to school at the Grand College.

Initially Petipa danced only to please his father who wanted to see him perform. However, he soon became enchanted with the art form and progressed so fast that he debuted at 9 in his father’s production of Pierre Gardel‘s La Dansomani. With the Belgian revolution forcing the family to move again, Jean Antoine secured a job as ballet master at the Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux. There, Petipa completed his training under the watchful eye of Auguste Vestris. By 1838, he had a job as Premier danseur in Nantes.

The following year Petipa and his father toured the United States performing for audiences who had never seen or known about ballet. While the tour was disastrous it had plenty of historical significance. Performing at the National Theatre in Broadway, Petipa was involved in the first ballet ever staged in New York City. From there Petipa travelled to Paris were he debuted at the Comédie-Française (or Théâtre-Français), partnering Carlotta Grisi and at the Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique (Paris Opéra).

In 1841 he returned to Bordeaux as a Premier danseur with the company, studying under Vestris while debuting in lead roles in Giselle and La Fille Mal Gardée. It was in Bordeaux that he started choreographing full-length productions. In 1843 he moved to the King’s Theatre in Madrid where he learnt about traditional Spanish Dancing which would come in handy for making character dances later on. He was forced to leave Spain after being challenged to a duel by a cuckolded husband, the Marquis de Chateaubriand, an important member of the French Embassy. Back in Paris, he took a position as Premier danseur at the Imperial Theatre of St. Petersburg where he arrived in 1847. His father soon followed, becoming a teacher at the Imperial Ballet School until his death in 1855.

Upon his arrival in St Peterburg, Petipa was recruited to assist in the staging of Joseph Mazilier‘s Paquita (originally staged at the Paris Opéra). Helped by his father, he also staged Mazilier’s Le Diable Amoureux. Both productions were praised and Petipa’s skills brought much needed respite to a company then in crisis.

Towards the end of 1850 Jules Perrot arrived as Premier Maître de Ballet (Principal ballet master) for the St. Petersburg Theatres. His main collaborator, composer Cesare Pugni, had also been appointed as Ballet Composer at the Imperial Theatres. Petipa danced the main roles in Perrot’s productions and served as his assistant, staging revivals such as Giselle (1850) and Le Corsaire (1858). In parallel Petipa started to choreograph dances for opera and to revise dances for Perrot’s productions.

Petipa was now choreographing more frequently, making ballets for his ballerina wife Maria Sergeyevna Surovshchikova. A rivalry with Arthur Saint-Léon, the new Principal ballet master after Perrot’s retirement (1860) developed, the two competing for the most successful production. But while Saint-Léon’s The Little Humpbacked Horse was very well received he flopped with Le Poisson Doré (1866) and Le Lys (1869) which led to his contract not being renewed. Not long afterwards Saint-Léon died of a heart attack leaving an opening for Petipa to fill the position of Premier Maître de Ballet (March, 1871).

Before being appointed ballet master Petipa had already:

- Had a huge success with La Fille du Pharaon (The Pharaoh’s Daughter, 1862), at that time the most popular ballet in the repertoire with over 200 performances by 1903;

- Revived Le Corsaire;

- Presented Le Roi Candaule at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre;

- Staged Don Quixote at the Moscow Imperial Bolshoi Theatre.

1898 photo of Petipa's ballet "The Pharaoh's Daughter", Mathilde Kschessinska as Princess Aspicia and Olga Preobrajenska as Ramzé the slave. Photo: Imperial Mariinsky Theatre.

When Don Quixote was lavishly restaged in St. Petersburg its composer Ludwig Minkus became official Ballet Composer of the Imperial Theatres, leading Petipa and Minkus into a fruitful collaboration, with La Bayadère (1877) becoming one of Petipa’s most celebrated works.

Minkus retired in 1886 and Director Ivan Vsevolozhsky did not seek a replacement official composer, allowing instead for more diversified ballet music. This paved the way for Tchaikovsky to collaborate with Petipa in The Sleeping Beauty (1889) and create one of the most successful classical ballets of all time. At that time Petipa was diagnosed with a skin disease which meant long periods away from work. For The Nutcracker (1892) Tchaikovsky worked with Petipa’s assistant Lev Ivanov who would frequently cover for Petipa together with Enrico Cecchetti.

The Mariinsky Ballet in Petipa's Le Reveil de Flore (The Awakening of Flora). Photo: Natasha Razina / Mariinsky Theatre ©

During his tenure as balletmaster Petipa also:

- supervised Ivanov and Cecchetti in the staging of Cinderella (1894) with italian virtuosa Pierina Legnani in the title role. Here she first performed the famous 32 fouettés en tournant later consecrated in Swan Lake;

- choreographed The Awakening of Flora (1894) with music by Riccardo Drigo;

- revived, together with Lev Ivanov, Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake (1895). Lev Ivanov worked on the second and fourth acts while Petipa was in charge of the rest. Together they turned this previously unsuccessful ballet into one of the all-time greatest;

- Continued working (coaching Anna Pavlova in her debut in Giselle) despite the deterioration of his health and persecution from new artistic director Vladimir Telyakovsky following an ill–received adaptation of Snow White (entitled Le Miroir Magique);

- Created a final ballet, L’Amour de la Rose et le Papillon, which was scrapped before its premiere by Telyakovsky due to the impending war with Japan.

Petipa retired to Gurzuf in southern Russia in 1907 at the suggestion of his doctors. He remained there until his death on July 14, 1910. A diary entry dated 1907 reads: “I can state I created a ballet company of which everyone said: St. Petersburg has the greatest ballet in all Europe.”

His Ballets

Petipa will be forever associated with lavish productions, character and classical dances, big ensemble and dramatic scenes in mime or in pas d’action (mime with dance). His dances combine the technical purity of the French school with the virtuosity of the Italian school. He was very involved in the creation of his ballets, researching subject matter extensively and working close with the composer and designer. He created choreography before going to the studio and teaching it to his dancers. He produced more than 46 original works and revised many more (e.g. Giselle), of which a large share is still being performed today.

Petipa’s ballets have survived more of less intact thanks to the availability of the Stepanov Method of notation from 1891 onwards. The method combines the encoding of dance movements with musical notes, in two steps: first, the breaking down of a complex movement and second, the translation of the broken down/basic movement into a musical symbol. The project was taken over by Alexander Gorsky and eventually by Nicholas Sergeyev, a former Imperial dancer, who later brought Giselle to the Paris Opéra Ballet and The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, Coppélia and The Nutcracker into The Royal Ballet. These notated versions became the standard choreographic text and have been adopted by nearly every major ballet company in the world.

A (non-exhaustive) list of his works

Original Works

- Le Carnaval de Venise (Pugni on a theme by Nicolò Paganini, 1858)

- The Pharaoh’s Daughter (Pugni, 1861)

- Don Quixote (Minkus, 1869)

- Les Aventures de Pélée (Minkus/Delibes, 1876)

- La Bayadère (Minkus, 1877)

- Roxana, la beauté de Monténégro (Minkus, 1878)

- Pygmalion ou La Statue de Chypre (Trubestkoi, 1883)

- La Fille Mal Gardée (with Lev Ivanov and Virginia Zucchi. Hertel / Hérold / Pugni, 1885)

- Les Pilules Magiques (Minkus, 1886)

- Le Talisman (Drigo, 1889)

- The Sleeping Beauty (Tchaikovsky, 1890)

- The Nutcracker (with Lev Ivanov – Tchaikovsky, 1892)

- Cendrillon (Staged by Ivanov and Cecchetti under Petipa’s supervision – Fitinhof-Schell, 1893)

- Swan Lake (with Lev Ivanov – Tchaikovsky revised by Drigo, 1895)

- Raymonda (Glazunov, 1898)

- Las Saisons (Glazunov, 1900)

- Le Millions d’Arlequin (Drigo, 1900)

- Le Miroir Magique (Koreschchenko, 1903)

- La Romance de la Rose et le Papillon (Drigo, never premiered)

Revivals/Restagings

- Paquita (after J. Mazilier with F. Malevergne – Deldevez / Liadov, 1847)

- Giselle (after J. Coralli and J. Perrot with Jules Perrot and Jean Petipa – Adam / Pugni, 1850)

- Le Corsaire (after J. Mazilier with J. Perrot – Adam / Pugni, 1858)

- Le Papillon (after M. Taglioni – Offenbach / Minkus 1874)

- Coppélia (after Saint-Léon – Delibes, 1884)

- La Esmeralda (after J. Perrot – Pugni 1886)

- La Sylphide (after F. Taglioni – Schnietzhoeffer/Drigo 1892)

- The Little Humpbacked Horse (after Saint-Léon – Pugni, 1895)

Videos

- Vikharev Reconstruction of Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty with Yevgenia Obraztsova as Aurora, Anton Korsakov as Prince Désiré and Anastasia Kolegova as The Lilac Fairy [link]

- Vikharev Reconstruction of Petipa’s La Bayadère with Daria Pavlenko as Nikiya, Igor Kolb as Solor and Elvira Tarasova as Gamzatti [link]

- Ratmansky and Burlaka‘s restaging of Le Corsaire for The Bolshoi, with Maria Alexandrova as Medora and Nikolai Tsiskaridze as Conrad [link]

- Dance of the Animated Frescoes from The Little Humpbacked Horse, performed by students of the Vaganova Academy. [link]

- Vikharev Reconstruction of The Awakening of Flora with Yevgenia Obraztsova as Flora, Xenia Ostreikovskaya as the Aurora, Vladimir Shklyarov as Zephyr, Maxim Chaschegorov as Apollo and Valeria Martynyuk as Cupid. [link]

- Pas de deux from Le Talisman by students from the Vaganova Academy [link]

- Pas de deux from La Fille Mal Gardée by students from the Vaganova Academy [link]

- Burlaka’s Reconstruction of the Paquita Grand Pas Classique with Svetlana Zakharova and Andrei Uvarov [link]

- Mikhailovsky Theatre‘s staging of the Grand Pas Classique from La Esmeralda [link]

- Ulyana Lopatkina as Odile and Danila Korsuntsev as Siegfried in Act III of Mariinsky’s Swan Lake [link]

Sources and Further Information

- Biography of Marius Petipa: His Life and Work. ArticleMyriad.com [link]

- Ballet Met Notes for Marius Petipa, Choreographer [link]

- Wikipedia entry for Marius Petipa [link]

- The Diaries of Marius Petipa. Edited and Translated by Lynn Garofola. Studies in Dance History, Society of Dance History Scholars. (1992) ASIN: B0006P1DJ6 [link]

- Russian Ballet Master: The Memoirs of Marius Petipa. Edited by Lillian Moore and Translated by Helen Whittaker. Dance Books LTD (2009) ISBN-10: 0903102005 [link]

- The Cambridge Companion to Ballet by Marion Kant. Cambridge University Press; 1st edition (2007). ISBN-10: 0521539862 [link]