Is this ballet for you?

Go If: You can’t resist a tragic love story. New Moon is your favorite book of the entire Twilight Saga and you can quote a certain passage from Act II, Scene VI of Shakespeare’s play by heart (don’t worry we won’t tell anyone). You’ve never been to the ballet and want to start with a tale that’s easy to follow in dance form.

Avoid If: Get thee gone, thou artless idle-headed pignut! (Ok, so you’re not a fan of The Bard)

Dream Casts

We asked our twitter followers and they said:

Juliet – Gelsey Kirkland, Yevgenia Obraztsova, Maria Kochetkova, Miriam Ould-Braham, Silvia Azzoni, Julie Kent, Alessandra Ferri, Alina Cojocaru

Romeo – Anthony Dowell, Vladimir Shklyarov, Igor Kolb, Jason Reilly, Friedemann Vogel, Angel Corella, Robert Fairchild, Steven McRae

Background

The Leonid Lavrovsky version

The idea for Romeo and Juliet as ballet came originally from Sergei Radlov, the Artistic Director of the Kirov (now the Mariinsky) around 1934. He developed the scenario together with theatre critic Adrian Piotrovsky and commissioned the music from one of his favorite Chess partners: Sergei Prokofiev who had never before composed for a full-length ballet.

Prokofiev finished the score on September, 1935 but the production was stalled when the communist regime demanded it be given a happy ending. Having shaped his score to match Radlov’s interpretation of the Shakespearean play Prokofiev was unhappy with this imposition.

Mariinsky's Vladimir Shklyarov and Yevgenia Obraztsova in Lavrovsky's Romeo and Juliet. Photo: Natalia Razina / Mariinsky Theatre ©

Further political problems saw the project shelved and transferred to the Bolshoi where it was deemed unsuitable. The ballet was eventually salvaged by the Kirov and on January 11, 1940 Romeo and Juliet finally received its premiere, with choreography by Artistic Director Leonid Lavrovsky. Legendary Galina Ulanova was the original Juliet and Konstantin Sergeyev her Romeo. The ballet was hailed a success but it only became a phenomenon six years later when it was staged in The Bolshoi Theatre (December 28, 1946), resulting in Lavrovsky’s appointment as Artistic Director of the Bolshoi.

The Bolshoi toured London for the first time and staged Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet in the Covent Garden Stage (October 3, 1956) to great acclaim. Margot Fonteyn expressed she had “never seen anything like it” and budding choreographer John Cranko was so inspired by the ballet that he soon started to plan his own version.

Mariinsky's Viktoria Tereshkina and Yevgeny Ivanchenko in Lavrovsky's Romeo and Juliet. Photo: Natalia Razina / Mariinsky Theatre ©

The John Cranko version

Cranko’s first staging of Romeo & Juliet was for the ballet company of La Scala in Milan in July 26, 1958. It was danced in an open amphiteatre in Venice. Designs were by Nicola Benois and the role of Juliet was danced by then 21 year-old Carla Fracci. Further revising the ballet Cranko staged it in 1962 for his own company, The Stuttgart Ballet. Jürgen Rose was in charge of the designs and young Brazilian ballerina Marcia Haydée, soon to become Cranko’s muse, was cast in the role of Juliet, with Richard Cragun as Romeo.

Cranko’s staging is renowned for its strong corps de ballet dances, which set the atmosphere. The first scene takes place in the cramped streets of Verona, so both Montagues and Capulets are incapable of avoiding each other. In Act II the fight erupts amongst peasants on a harvest festival, with everyone involved and fruits being spilled around. At that time Cranko’s company were still developing their technique and identity so the choreography is relatively simple. When it comes to the various pas de deux one can see Lavrovsky’s influence in the very Soviet style of partnering with lifts and tosses.

Cranko’s version of Romeo and Juliet remains very popular and besides being a regular staple at the Stuttgart Ballet, it is also in repertory at The National Ballet of Canada, The Australian Ballet, Finnish National Ballet, The Joffrey, Houston Ballet, Boston Ballet, and Pensylvannia Ballet, among others.

The Kenneth MacMillan version

Kenneth MacMillan, a close friend of Cranko’s from their dancing days in the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, was inspired to create his own version for The Royal Ballet after seeing it staged by The Stuttgart Ballet. An opportunity came when The Royal Opera House failed to secure a deal with the Bolshoi to exchange performance rights for Ashton‘s La Fille Mal Gardée against Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. Ninette de Valois had also asked Sir Frederick Ashton to stage the version originally choreographed for The Royal Danish Ballet in 1955 but he feared that something created for a smaller theatre would look modest compared to the scale of the Russian production. Ashton, then Artistic Director, suggested to the Board of Directors that MacMillan should undertake the task of creating a new version.

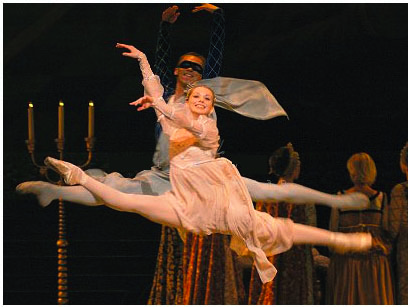

Steven McRae and Alina Cojocaru in The Royal Ballet's production of MacMillan's Romeo & Juliet. Photo: Bill Cooper / ROH ©

MacMillan had devised a balcony scene pas de deux for Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable for a feature on Canadian television and once he received the go-ahead he started working on his first full-length ballet, nowadays one of Romeo and Juliet’s most definitive versions.

Designer Nicholas Georgiadis was inspired by Franco Zeffirelli‘s production of the Shakespearean tragedy for the Old Vic, in which the Capulets lived in a big fortress-like mansion. MacMillan wanted his ballet to be more realistic than romantic, with added contemporary touches. He wanted the young lovers to die painfully and to drop the reconciliation between Capulets and Montagues at the end of the play providing a different angle from the Lavrovsky & Cranko versions.

The ballet was choreographed on Seymour and Gable as Juliet and Romeo. As usual, MacMillan explored the role of the outsider in his portrayal of Juliet, a headstrong and opinionated girl who breaks away from her family. He started with the pas de deux (the highlights of this staging) and drew on the full company plus extras to set the town scenes.

While work was in progress Covent Garden management delivered the blow that Fonteyn and Nureyev would be first cast Juliet and Romeo, a shock to MacMillan, to Ashton (who had expected them as a first cast for the US tour only) and to dancers Seymour and Gable who had to teach their roles and resign themselves to a lower spot on the bill.

MacMillan’s pleas to Covent Garden management to keep Seymour and Gable in the premiere were in vain. His Romeo and Juliet premiered on February 9, 1965, with Fonteyn and Nureyev taking 43 curtain calls over a 40 minute applause. In the US it quickly became the best known version of the Prokofiev ballet. Besides the Royal Ballet, the ballet is also part of the regular repertory of American Ballet Theatre, The Royal Swedish Ballet and Birmingham Royal Ballet (with designs by Paul Andrews).

Story

You probably don’t need our help with this one. Regardless of version the storyline remains more or less the same:

Act I

Scene 1. The Market Place in Verona

It’s early hours in Verona. Romeo unsucessfully tries to woo Rosaline and is consoled by his friends Mercutio and Benvolio. As the market awakens and street trading starts a quarrel breaks out between the Montagues and the Capulets. Tybalt, Lord Capulet’s nephew, provokes Romeo’s group and the sword fighting begins with both Lord Montague and Lord Capulet joining in. Escalus, the Prince (or Duke) of Verona, enters and commands the families to cease fighting and issues a death penalty for any further bloodshed.

Scene 2. Juliet and her Nurse at the Capulet House

Lord Capulet’s only daughter Juliet is playing with her nurse. Her parents enter her chambers and inform Juliet of her impending engagement to the wealthy noblement Paris to whom she is to be formally introduced at the evening’s ball. In MacMillan’s version Juliet’s introduction to Paris happens at this point.

Scene 3. Outside the Capulet House

Guests are seen arriving at the Capulets’. Romeo, still in pursuit of Rosaline, makes his way into the ball in disguise accompanied by Mercutio and Benvolio.

Scenes 4 & 5. The Ballroom & Outside the Capulet House

At the ball all eyes are on Juliet as she dances with her friends. Romeo becomes so entranced by her that he completely ignores Mercutio’s attempts to distract him. As Juliet starts to notice Romeo his mask falls. Juliet is immediately bewitched but Tybalt recognises Romeo and orders him to leave. Lord Capulet intervenes and welcomes Romeo and his friends as guests. At this point in MacMillan’s staging we see inebriated guests leaving and Lord Capulet stopping Tybalt from pursuing Romeo.

Scene 6. Juliet’s Balcony

Later that night Juliet is unable to sleep and stands on her balcony thinking about Romeo. Just then he appears on the garden below and they both dance a passionate pas de deux where they express their mutual feelings.

Mariinsky's Vladimir Shklyarov and Yevgenia Obraztsova in Lavrovsky's Romeo and Juliet. Photo: Natalia Razina / Mariinsky Theatre ©

Act II

Scenes 1 & 2. The Market Place & Friar Laurence’s Chapel

As festivities are being held at the marketplace Romeo daydreams about getting married to Juliet. His reverie is broken when Juliet’s nurse makes her way through the crowds bringing him Juliet’s letter with the acceptance to his proposal. The young couple is secretly married by Friar Laurence, who hopes the union will end the conflict between their respective families.

Scene 3. The Market Place

Tybalt enters interruping the festivities. He provokes Romeo, who now avoids the duel, realising he is now part of Juliet’s family. Mercutio is willing to engage with Tybalt and, in vain, Romeo attempts to stop them. Mercutio is fatally wounded by Tybalt. Romeo seeking to avenge his friend’s death finally yields to Tybalt’s provocations and kills him. Romeo must now flee before being discovered by Prince of Verona. Curtains close as Lady Capulet grieves over Tybalt’s dead body and her breakdown is particularly emphasised in Cranko’s staging.

José Martín as Mercutio and Thiago Soares as Tybalt in The Royal Ballet's production of MacMillan's Romeo and Juliet. Photo: Dee Conway / ROH ©

Act III

Scene 1. Juliet’s Bedroom

Romeo has spent his last night in Verona with Juliet but as dawn arrives he must flee for Mantua despite her pleas. To Juliet’s dismay Lord and Lady Capulet appear together with Paris to start preparations for the wedding. Juliet refuses to marry Paris and Lord Capulet threatens to disown her. In despair, Juliet seeks Friar Laurence’s counsel.

Scenes 2 & 3. Friar Laurence’s Chapel & Juliet’s Bedroom

Juliet begs Friar Laurence for help. He gives Juliet a sleeping potion that will make her fall into a deathlike sleep. This will make everyone believe Juliet is dead while the Friar will send for Romeo to rescue her. Juliet returns home and agrees to marry Paris. She drinks the potion and falls unconscious. Her friends and parents arrive the next morning and discover her lifeless.

Scene 4. The Capulet Family Crypt

Romeo has heard of Juliet’s death (in the Lavrovsky version we see Romeo break down in grief as the news are delivered to him) and has returned to Verona without having received Friar Laurence’s message. He enters the crypt disguised as a monk where he finds Paris by Juliet’s body. Stunned by grief, Romeo kills Paris (this is absent from Lavrovsky’s staging). Still believing Juliet to be dead Romeo drinks a vial of poison and collapses. Juliet awakes to find Romeo dead beside her. She stabs herself to join Romeo in death.

Epilogue (Lavrovsky version)

Both Montagues and Capulets gather together and reconcile before their children’s bodies.

Lauren Cuthbertson and Edward Watson in The Royal Ballet's production of MacMillan's Romeo & Juliet. Photo: Dee Conway / ROH ©

Videos:

- Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev in the Balcony pas de deux, MacMillan version [link]

- Lynn Seymour and David Wall in the Bedroom Pas de Deux, MacMillan version [link]

- A playlist featuring Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet [link]

- Yevgenia Obraztsova and Vladimir Shklyarov in the Balcony Pas de Deux, Lavrovsky version [Part 1] and [Part 2]

- A playlist featuring Marcia Haydée and Richard Cragun in Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet [link]

- Marcia Haydée and Richard Cragun in the Bedroom pas de deux Cranko version [link]

Other versions

Prokofiev’s masterful composition for Romeo and Juliet is now better known than any other but a number of earlier and later productions of the ballet have been set to different scores and choreography:

-

Antony Tudor‘s Romeo and Juliet for Ballet Theatre, now ABT (1943), set to various pieces of music by Frederick Delius.

-

Sir Frederick Ashton’s Romeo and Juliet for The Royal Danish Ballet (1955). This is a signature Ashton piece with none of Lavrovsky’s influence (as Ashton had not yet seen that staging). Clips of the revival by London Festival Ballet with Katherine Healy as Juliet can be found here [link]

-

Maurice Béjart‘s Romeo and Juliet (1966). Set to the music of Berlioz this version was presented at the Cirque Royal, Brussels. A video featuring Suzanne Farrell as Juliet and Jorge Donn as Romeo can be found here [link]

-

Rudolf Nureyev’s version for the London Festival Ballet (1977). Nureyev later reworked this same version for the Paris Opera Ballet (1984). The ballet is available on DVD with Monique Loudieres as Juliet and Manuel Legris as Romeo. Clips can be seen here [link]

-

John Neumeier‘s for the Frankfurt Ballet (1971). This version was restaged for his own Hamburg Ballet in 1974. It has also been further revised and staged by The Royal Danish Ballet. Clips can be seen here [link]

-

Yuri Grigorovich‘s version for the Bolshoi (1982) set to Prokofiev’s score. This version is still danced by the company.

-

Jean Christophe Maillot‘s Rómeo et Juliette for Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo (1996). This version has been staged by other companies, most recently by Pacific Northwest Ballet. A trailer can be found in PNBallet’s YT channel [link]

-

Peter Martins’s Romeo + Juliet for NYCB (2007). A series of videos following the ballet’s creative process can be found on NYCB‘s channel [link]

Music

Prokofiev’s score for Romeo and Juliet is considered one of the four greatest orchestral compositions for ballet (together with Tchaikovsky’s scores for Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker). He originally conceived the score as 53 sections linked by the dramatic elements of the story, each section named after the characters and/or situations in the ballet.

Like Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev developed leitmotifs for the characters. There are 7 themes for Juliet varying from her playful/girlish side in Act I to romantic and dramatic themes which follow her development into a woman in love and foreshadow the impending tragedy in Act III.

A quintessential Spotify / iPod playlist should include the three orchestra suites (Opus 64bis, Opus 64ter and Opus 101)

- Suite No 1. Folk Dance, The Street Awakens, Madrigal, The Arrival of Guests, Masks, Romeo and Juliet, Death of Tybalt.

- Suite No 2. Montagues and Capulets, Juliet the Young Girl, Dance, Romeo and Juliet before parting, Dance of the Girls with Lilies, Romeo at Juliet’s Grave.

- Suite No 3. Romeo at the Fountain, Morning Dance, Juliet, The Nurse, Morning Serenade, The Death of Juliet.

Mini-Biography

Choreography: Leonid Lavrovsky

Music: Sergei Prokofiev

Designs: Pyotr Williams

Original Cast: Galina Ulanova as Juliet and Konstantin Sergeyev as Romeo

Premiere: January 11, 1940, Kirov Theatre, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg).

Choregraphy: John Cranko

Music: Sergei Prokofiev

Designs: Jürgen Rose

Original Cast: Marcia Haydée as Juliet and Richard Crangun as Romeo

Premiere:December 2, 1962, Stuttgart.

Choreography: Kenneth MacMillan

Music: Sergei Prokofiev

Designs: Nicholas Georgiadis

Original Cast: Margot Fonteyn as Juliet and Rudolf Nureyev as Romeo

Premiere:February 9, 1965 at Covent Garden, London.

Sources and Further Information

- The Royal Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet (Kenneth MacMillan) Programme Notes, 2007/2008 Season.

- Romeo & Juliet entry at www.KennethMacmillan.com [link]

- Wikipedia entry for Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet score [link]

- Romeo and Juliet Notes (John Cranko) from National Ballet of Canada [link]

- Notes from Tbsili Opera and Ballet Theatre [link]

- Ballet Met Notes [link]

- Stuttgart Ballet Performance Notes at Cal Performances [link]

- Dedicated Romeo and Juliet. Dance review by Anna Kisselgoff. New York Times, July 1998 [link]

- From London, a Poetic Romeo that makes others seem prosy. Dance review by Anna Kisselgoff. New York Times, 1989 [link]

- Romeo and Juliet, Theatricality and Other Techniques of Expression by Katherine S. Healy. Following Sir Fred’s Steps, Ashton’s Legacy. Edited by Stephanie Jordan and Andrée Grau. Conference Proceedings, 1994 [link]

- Opposing Houses: Judith Mackrell on visions of Romeo and Juliet from Ashton and MacMillan. Dance review, The Independent. August, 1994 [link]